Metro Atlanta’s overdose crisis continues to evolve with a complicated mix of modest improvements and persistent risks.

Fentanyl remains the leading driver of fatal overdoses across the region, and provisional 2024 data from counties like Cobb show tentative declines even as middle-aged Black men face rising mortality.

This article explains what recent surveillance tells us about each county, who remains most at risk, and how to interpret conflicting signals from different data sources.

Metro Atlanta Overdose Trends Through 2025

The Metro Atlanta region entered 2025 with mixed signals. National data showed the U.S. age-adjusted overdose death rate declined from 2022 to 2023, and some local indicators suggest similar stabilization across parts of the metro area.

Fulton, DeKalb, Cobb, Gwinnett, and surrounding counties experienced a steep climb in deaths from 2020 through 2022, driven almost entirely by illicitly manufactured fentanyl infiltrating the drug supply. Since 2020, overdoses have surged in Georgia due to fentanyl’s presence in heroin, cocaine, methamphetamine, and counterfeit pills.

Yet beneath the regional averages, important differences emerge. Cobb County’s health department reported the first declines or steady rates since 2019 across multiple age groups in 2023, with provisional signals extending into 2024. Meanwhile, research projects that overdose deaths among Black men ages 31 to 64 will continue to increase through 2025, especially in large urban counties like Fulton and DeKalb. This means aggregate improvement can mask worsening inequities.

The most reliable county-level data comes from two complementary systems. Georgia’s OASIS mortality tool provides final, residence-based death counts and age-adjusted rates through the most recent finalized year, typically lagging by about 18 months.

The CDC’s Vital Statistics Rapid Release publishes provisional county counts updated monthly, offering more timely signals but with incomplete reporting that underestimates true totals. Understanding this gap matters when interpreting 2024 and 2025 trends, because provisional counts will rise as investigations close.

Fentanyl and Polysubstance Use Drive Deaths

Fentanyl reshaped Metro Atlanta’s overdose landscape starting around 2016 and accelerating sharply through the pandemic years. Georgia reported a 308 percent increase in fentanyl-involved deaths from 2019 to 2022, jumping from 392 to 1,601.

What makes fentanyl especially dangerous in Atlanta is its infiltration of stimulants. People who use cocaine or methamphetamine now face opioid overdose risk even when they do not intentionally seek opioids, because dealers cut their products with fentanyl to boost potency or stretch supply.

Stimulant involvement has grown substantially. Nationally, cocaine-involved deaths roughly doubled from 2018 to 2023, and psychostimulants like methamphetamine showed similar sharp increases.

In Metro Atlanta, where cocaine markets have long been established, this polysubstance pattern means many overdose deaths involve both fentanyl and cocaine or both fentanyl and methamphetamine. Nearly 60 percent of U.S. overdose deaths from January 2021 through June 2024 involved at least one stimulant.

This shift demands a different prevention approach. Distributing naloxone only to people who identify as opioid users misses the large share of stimulant users now at risk. Fentanyl test strips help people check their drugs before use, and harm reduction programs should reach stimulant-using networks, not just traditional opioid treatment settings.

The Georgia Department of Public Health operates syringe service programs and naloxone distribution initiatives designed to serve this broader at-risk population, though coverage remains uneven across metro counties.

Xylazine, a veterinary sedative, has also appeared in Georgia’s overdose surveillance from 2020 through 2022. While the magnitude in Metro Atlanta remains uncertain, xylazine complicates overdose response because it does not respond to naloxone. This underscores the need for rapid transport to emergency care and broader harm reduction education beyond opioid-focused messaging.

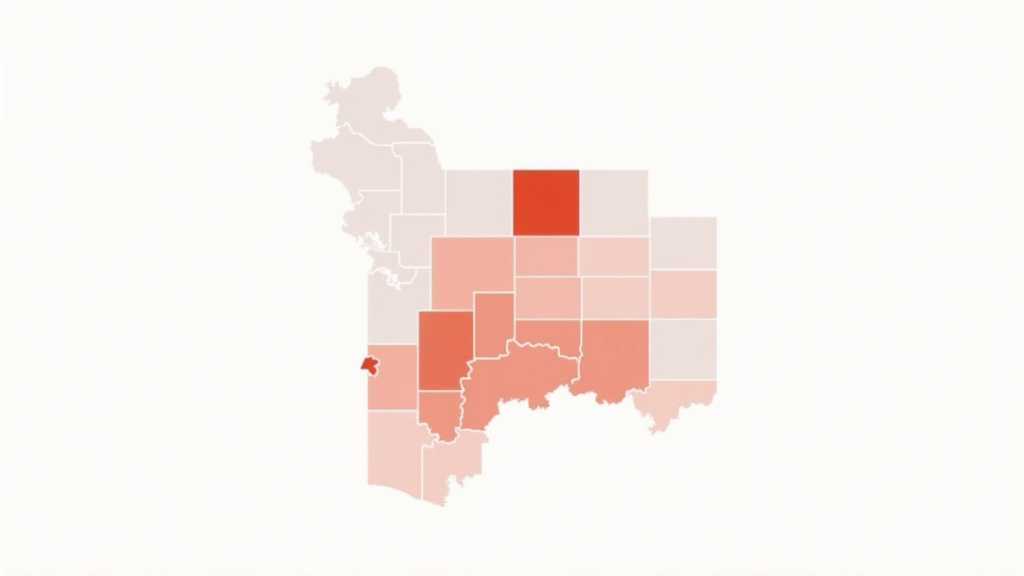

County-Level Patterns in Metro Atlanta Overdose

Fulton County

Fulton County reported 154 opioid-related deaths in 2016, a 156 percent increase since 2010 and a rate exceeding the national average at the time. As Georgia’s most populous county and home to Atlanta’s urban core, Fulton serves as a regional medical hub, meaning some deaths occurring in Fulton hospitals involve residents of other counties. This complicates occurrence-based counts but does not change the fact that Fulton residents face high overdose mortality.

Fulton likely peaked in deaths around 2021 or 2022, consistent with national fentanyl trends. The county established an opioid coordinator and expanded medication disposal sites, naloxone access, and partnerships with Grady Behavioral Health for medications for opioid use disorder. Still, middle-aged Black men remain at elevated risk through 2025, and income inequality within Fulton correlates with higher overdose rates in disadvantaged neighborhoods.

DeKalb County

DeKalb mirrors Fulton’s trajectory as a large, diverse urban county adjacent to Atlanta’s core. Fentanyl-driven increases likely accelerated from the mid-2010s, with particularly sharp rises from 2020 to 2022. Cocaine involvement has historically been relevant in the metro area, and polysubstance deaths involving both fentanyl and cocaine are common. Racial disparities are pronounced, with Black adults in large central metro settings experiencing steep increases in synthetic opioid mortality.

Targeted harm reduction efforts in high-burden neighborhoods, especially those with concentrated economic disadvantage, are essential for DeKalb. This means placing naloxone and fentanyl test strips in places frequented by men in their 30s and 40s, such as transit hubs, community centers, and workplaces, and ensuring that medication for addiction treatment is available on demand without waiting lists or bureaucratic hurdles.

Cobb County

Cobb County experienced some of the region’s highest prescription opioid deaths in 2016, then saw fentanyl take over as the primary driver. Local health department data show that 2023 brought the first declines or stabilization across several age groups since 2019, with provisional evidence suggesting continued improvement into 2024. Fentanyl involvement remains high but appeared to decrease slightly in 2023.

Despite these positive signals, risk persists. The age group with the highest opioid overdose rate in Cobb is 35 to 44 years old, consistent with national middle-age concentration. Increases among Hispanic residents in recent data highlight the need for culturally tailored outreach. Sustaining recent gains requires maintaining naloxone saturation, expanding low-barrier buprenorphine access, and monitoring near-real-time emergency department and EMS overdose indicators for any re-acceleration.

Gwinnett County

Gwinnett’s drug poisoning death rate from 2020 to 2022 was 16.1 per 100,000, below both the Georgia state rate of 21.9 and the U.S. rate of 27.2, meeting the Healthy People 2030 target. Gwinnett is now one of the region’s most diverse counties, with substantial Hispanic, Asian, and Black populations. This diversity requires attention to race and ethnicity in surveillance, as national data suggest modest underestimation of overdose rates among Hispanic and Asian groups due to death certificate misclassification.

Fentanyl and polysubstance risks still threaten Gwinnett despite its comparatively lower overall rates. Prevention infrastructure, including naloxone distribution, culturally competent treatment engagement, and monitoring for shifts in stimulant co-involvement, should continue. County officials should verify recent 12-month trends using the CDC’s provisional county dataset to catch any emerging increases early.

Douglas County

Douglas County’s opioid overdose rate reached 18.8 per 100,000 in 2016, among the highest in the region. The Cobb and Douglas Public Health district reports that the 35 to 44 age group continues to show the highest overdose rates, aligning with the middle-age risk concentration seen across the country. Small subgroup counts are sometimes suppressed due to low numbers, limiting detailed race and ethnicity analysis.

The priority for Douglas is middle-aged adults, especially men, who should receive persistent naloxone distribution and rapid linkage to medication-assisted treatment. Emergency medical services and syndromic surveillance from emergency departments provide near-real-time trend signals that can guide rapid public health response when clusters emerge.

Cherokee, Clayton, Fayette, Henry, Rockdale

Northern suburbs like Cherokee saw sharp increases through 2016, part of what regional analysts called a deadly triangle of rising opioid mortality. Peripheral counties experienced the spread of fentanyl and stimulant co-involvement through the late 2010s and early 2020s, though with heterogeneity across the metro ring. Each county’s 2025 trajectory should be validated with updated provisional counts and final OASIS data as they become available.

Income inequality and structural disadvantage within these counties likely shape localized overdose clusters. County health departments can use neighborhood-level mapping to identify hot spots and direct resources accordingly. Coordinated regional strategies, such as shared naloxone procurement and cross-county treatment referral networks, help ensure that residents in smaller counties receive the same standard of care as those in large urban centers.

Disparities Deepen Among Black Residents

The most troubling feature of Metro Atlanta’s overdose trends is the widening gap between Black residents and other groups. From 2019 to 2020, overdose rates rose fastest for Black and American Indian or Alaska Native populations nationally.

In counties with higher income inequality, overdose rates for Black people were more than twice those in counties with less inequality. Fulton and DeKalb, as large central metro counties with substantial Black populations and pockets of concentrated disadvantage, fit this pattern.

Projections using CDC data suggest overdose deaths among non-Hispanic Black men will increase significantly through 2025 for those ages 31 to 47 and 48 to 64. Younger Black men in their late teens and twenties saw mortality flatten after a pandemic-era spike, but the burden is shifting to middle-aged men.

This age and demographic pattern demands precise targeting. Harm reduction materials, naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and low-barrier treatment must reach the places these men live, work, and gather.

Why are middle-aged Black men at such high risk? Structural factors include higher rates of incarceration, which disrupts treatment continuity and resets tolerance upon release. Economic inequality limits access to health insurance and quality care. Stigma around addiction and mental health in some communities delays help-seeking. The drug supply itself has become more dangerous, with fentanyl adulteration of cocaine, a substance with established use patterns in Black communities. Addressing these overlapping vulnerabilities requires community-engaged strategies, not just clinical interventions.

Hispanic communities in Cobb and other diversifying suburbs also saw recent increases, underscoring the need for Spanish-language outreach, culturally competent providers, and trust-building with immigrant populations who may fear interaction with health systems due to documentation status.

Asian and American Indian or Alaska Native populations face underestimation in mortality data due to race misclassification on death certificates, meaning published rates may understate their true burden by up to 34 percent for AI/AN people and about 3 percent for Asian and Hispanic people.

What to Watch in Late 2025?

Several developments will clarify whether the tentative improvements seen in some counties represent durable declines or temporary plateaus.

- Finalized 2024 data: When Georgia OASIS and CDC NVSS publish final 2024 county mortality data in mid to late 2025, analysts will confirm whether provisional declines observed in Cobb and other counties hold up. Provisional counts typically underestimate final totals because investigations take time to close, so we should expect some upward revision.

- Age and race patterns: Detailed stratifications by age group and race/ethnicity in final data will show whether the Harris projection of rising mortality among middle-aged Black men materialized or whether targeted interventions blunted that trajectory.

- Drug involvement trends: The CDC’s State Unintentional Drug Overdose Reporting System provides detailed toxicology data on which substances appear in fatal overdoses. Tracking fentanyl, cocaine, methamphetamine, and xylazine co-involvement through 2025 reveals whether the polysubstance pattern is intensifying or stabilizing.

- EMS and emergency department indicators: Near-real-time syndromic surveillance from emergency departments and EMS runs for overdose offer early warning signals. Georgia changed its EMS case definition in November 2023, so comparisons across that date require caution, but within-period trends can detect emerging hot spots or demographic shifts.

- Policy and funding changes: Georgia’s allocation of opioid settlement funds, Medicaid expansion discussions, and county-level investments in harm reduction and treatment capacity all influence outcomes. Fulton’s regional advisory council for opioid settlement spending exemplifies the kind of coordinated resource deployment that can accelerate progress.

- One important methodological note: OASIS updated its overdose mortality definition in 2018 to align with CDC standards, adding certain opioid codes and limiting counts to acute poisonings rather than chronic drug-related conditions. This created a small step-up in reported deaths around 2018 that reflects definitional change, not just epidemiologic reality. Analysts comparing 2016 to 2025 should annotate this inflection point to avoid overstating the increase.

Moving Forward with Evidence and Equity

Metro Atlanta’s counties face a dual challenge. They must sustain recent progress where declines or stabilization have appeared, while simultaneously closing the equity gaps that leave Black men in their 30s, 40s, and 50s at unacceptably high risk. Three strategies offer the highest return on investment.

Targeted harm reduction for high-burden groups: Saturate naloxone, fentanyl test strips, and overdose response education in neighborhoods and networks where middle-aged Black men live and spend time. Partner with barber shops, churches, community organizations, and employers to distribute materials and reduce stigma. Pair immediate life-saving tools with pathways to treatment that do not require insurance, sobriety, or bureaucratic intake processes.

Expand low-barrier medication for opioid use disorder: Buprenorphine and methadone save lives, but only if people can access them quickly and without shame. Same-day or next-day initiation, telemedicine options, and co-location with primary care or harm reduction sites all improve uptake. County health departments should track MOUD coverage rates and identify gaps by geography and race.

Build transparent, near-real-time dashboards: Metro Atlanta lacks a single integrated overdose surveillance portal that combines fatal and nonfatal data, drug class breakouts, and methods documentation. King County, Washington, publishes exemplary dashboards with monthly updates, data quality indicators, and detailed analytic notes. Atlanta’s counties could adopt a similar model, integrating OASIS final data, VSRR provisional signals, EMS and emergency department syndromic data, and SUDORS toxicology trends into one public-facing platform updated quarterly with annual methods reports.

These are not speculative recommendations. They reflect best practices documented in CDC guidance, peer-reviewed literature, and successful local programs. The question is not what to do, but whether Metro Atlanta’s stakeholders will act with urgency proportional to the continuing toll.

The region’s overdose mortality in 2025 will not be defined by a single number or trend line. It will be measured by how effectively counties protect the people facing the highest risk, close the gaps that allow some neighborhoods and communities to suffer disproportionately, and turn surveillance data into swift, equitable action. Fentanyl remains dominant, stimulants are deeply entangled, and middle-aged Black men need focused support right now.

If you or someone you care about is struggling with substance use, effective help is available. Proven therapies like cognitive behavioral therapy, medication-assisted treatment, and community-based support can make recovery possible. Reach out to learn about our therapeutic programs that combine structure, peer support, and evidence-based care tailored to your needs.