Does Vyvanse Make You Sweat? Vyvanse Sweating & Body Odor Explained

Many people taking Vyvanse notice they sweat more than usual, especially under the arms. This side effect can feel embarrassing and uncomfortable, but it is not random.

Vyvanse increases your body’s arousal and heat production, which can trigger your sweat glands to work harder.

In this article, you will learn why Vyvanse can cause sweating, how to tell if your symptoms need urgent attention, and practical steps to manage both sweat and odor without giving up your ADHD treatment.

Why Vyvanse Can Increase Sweating?

Vyvanse is a prodrug that converts to d-amphetamine in your bloodstream. This active form raises levels of dopamine and norepinephrine in your brain, improving focus and impulse control.

However, these same chemical changes also increase sympathetic nervous system activity, which can elevate your heart rate, blood pressure, and metabolic heat production.

Your body responds to this extra heat by activating sweat glands to cool you down. Although sweat itself is controlled by acetylcholine acting on muscarinic receptors, the increased arousal and thermogenic demand from Vyvanse can indirectly drive more sweating. This is especially true during physical activity, stress, or in warm environments.

Importantly, sweating is not listed among the most common side effects in adult ADHD trials of Vyvanse.

The most frequent complaints include decreased appetite, insomnia, dry mouth, diarrhea, and nausea. This means that while some people do experience increased sweating, it is not a typical or dose-limiting problem for most users.

Individual Factors That Amplify Sweating

Several factors can make sweating worse on Vyvanse:

- Caffeine intake: Excessive caffeine from coffee, energy drinks, or supplements adds to stimulant effects. The Physicians’ Desk Reference specifically warns that too much caffeine can worsen nervousness, insomnia, and tremor, which often occur alongside sweating.

- Serotonergic medications: Combining Vyvanse with SSRIs, SNRIs, or certain pain medications can increase the risk of serotonin syndrome, a serious condition where diaphoresis is a key symptom.

- CYP2D6 inhibitors: Drugs like fluoxetine or paroxetine can raise d-amphetamine levels, potentially increasing side effects including sweating.

- Heat and activity: Warm weather, exercise, or heavy clothing naturally increase sweat output, which Vyvanse can amplify.

How Vyvanse Sweating Differs From Primary Hyperhidrosis?

Understanding the pattern of your sweating helps guide treatment. Primary hyperhidrosis is a chronic condition that usually starts early in life and affects specific areas like the palms, soles, underarms, or face. It tends to be symmetric, worse during the day, and improves at night.

Drug-induced sweating from Vyvanse often looks different. It may be more generalized across the body, can persist during sleep, and typically starts or worsens after beginning the medication or increasing the dose. According to DermNet, these temporal and distribution patterns help distinguish medication-related sweating from primary hyperhidrosis.

If your sweating is mainly in the armpits and accompanied by noticeable odor, you may have an underlying tendency toward axillary hyperhidrosis that Vyvanse has unmasked or worsened. This pattern responds well to targeted underarm treatments.

When Sweating Signals a Serious Problem?

Sweating alone is usually not dangerous, but it can be an early warning sign of serotonin syndrome when Vyvanse is combined with other medications.

Serotonin syndrome is a potentially life-threatening condition caused by too much serotonin activity in the brain and body.

Key symptoms include:

- Profuse sweating (diaphoresis)

- Fever or elevated body temperature

- Rapid heart rate and high blood pressure

- Muscle twitching, tremor, or clonus (rhythmic muscle jerks)

- Agitation, confusion, or restlessness

- Diarrhea

A recent analysis of over 13,000 serotonin syndrome reports found that combinations of SSRIs with SNRIs, tramadol, fentanyl, or MAO inhibitors carry especially high risk.

About 8% of reported cases were fatal. The Vyvanse label instructs doctors to start with lower doses and monitor closely when combining Vyvanse with serotonergic drugs or CYP2D6 inhibitors.

If you develop sweating along with fever, muscle jerking, confusion, or diarrhea after starting or increasing Vyvanse or another medication, seek medical attention immediately.

Understanding Vyvanse and Body Odor

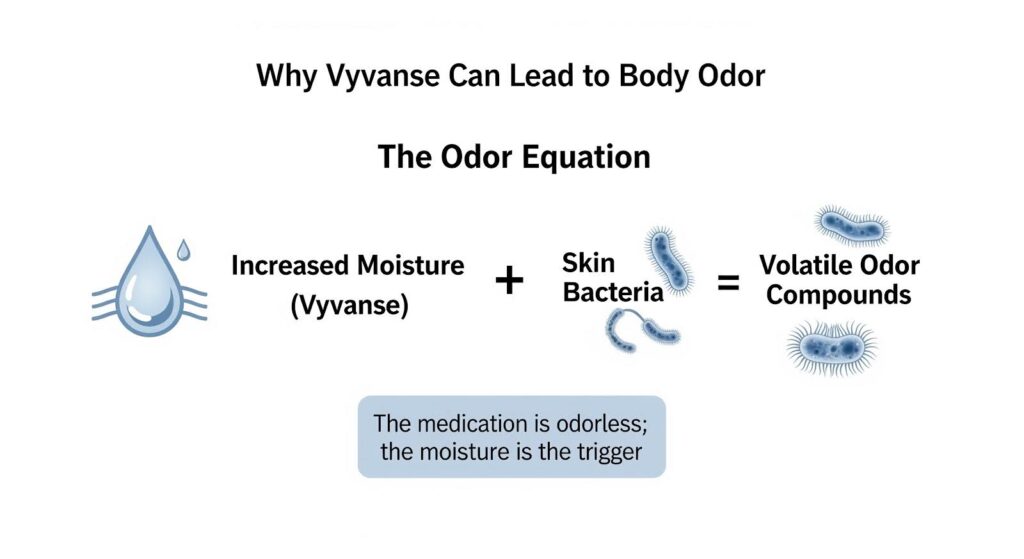

Body odor on Vyvanse is not caused by the medication directly changing your sweat chemistry. Instead, it results from increased moisture in the armpits creating a better environment for bacteria to break down sweat components into smelly compounds.

Your underarms contain three types of glands. Eccrine glands produce watery sweat for cooling. Apocrine glands secrete a thicker, lipid-rich fluid that bacteria metabolize into odor.

Apoeccrine glands, which develop during adolescence, can produce large volumes of watery sweat in the armpits. When Vyvanse increases overall sweat output, the extra moisture allows bacteria to thrive and produce more volatile odor compounds.

This explains why many people report that Vyvanse makes them sweat and smell worse, even though the medication itself is odorless. The solution is to reduce moisture and bacterial activity in the armpits.

How to Stop Sweating on Vyvanse: A Step-by-Step Plan?

Step 1: Remove Triggers and Optimize Your Dose

Start by eliminating factors that amplify sweating:

- Review your medications: Ask your doctor if any serotonergic drugs or CYP2D6 inhibitors can be adjusted or replaced.

- Cut back on caffeine: Switch to decaf or low-caffeine options. Avoid energy drinks and check labels on pain relievers for hidden caffeine.

- Adjust timing: Taking Vyvanse earlier in the day may help if sweating peaks in the afternoon. Taking it with food delays the peak effect by about an hour without reducing total exposure.

- Consider dose reduction: If sweating started after a dose increase, ask your doctor if stepping back to the previous dose still controls your ADHD symptoms.

Step 2: Start With Topical Antiperspirants

Aluminum chloride 20% solution is the first-line treatment for excessive underarm sweating. Apply it at night to completely dry skin. The aluminum salts temporarily block sweat ducts.

Once sweating is controlled, you can reduce application frequency to a few times per week for maintenance.

If over-the-counter clinical-strength antiperspirants are not enough, ask your doctor for a prescription-strength formula.

Proper technique matters: apply to dry skin before bed, avoid shaving immediately before application, and use a moisturizer if irritation develops.

Step 3: Add Topical Anticholinergic Therapy

If antiperspirants alone do not control sweating, topical anticholinergic medications offer a targeted solution. Glycopyrronium tosylate 2.4% cloth is FDA-approved for axillary hyperhidrosis in people aged 9 and older.

Randomized trials show it significantly reduces sweat production and improves quality of life, with mild side effects like dry mouth, temporary pupil dilation, and local irritation.

Another option is sofpironium bromide gel, which received FDA approval in 2024. A Japanese phase 3 trial found that 54% of patients achieved meaningful sweat reduction compared to 36% with placebo.

Both medications work by blocking acetylcholine receptors at the sweat gland, directly reducing sweat output without affecting your ADHD medication.

Step 4: Improve Hygiene and Odor Control

To reduce body odor while managing sweat:

- Use antibacterial washes containing benzoyl peroxide or chlorhexidine several times per week

- Trim or remove underarm hair to reduce bacterial niches

- Wear moisture-wicking fabrics and change shirts frequently

- Apply clinical-strength deodorant over your antiperspirant

- Consider absorbent underarm pads for extra protection

Step 5: Consider Procedural Options for Lasting Relief

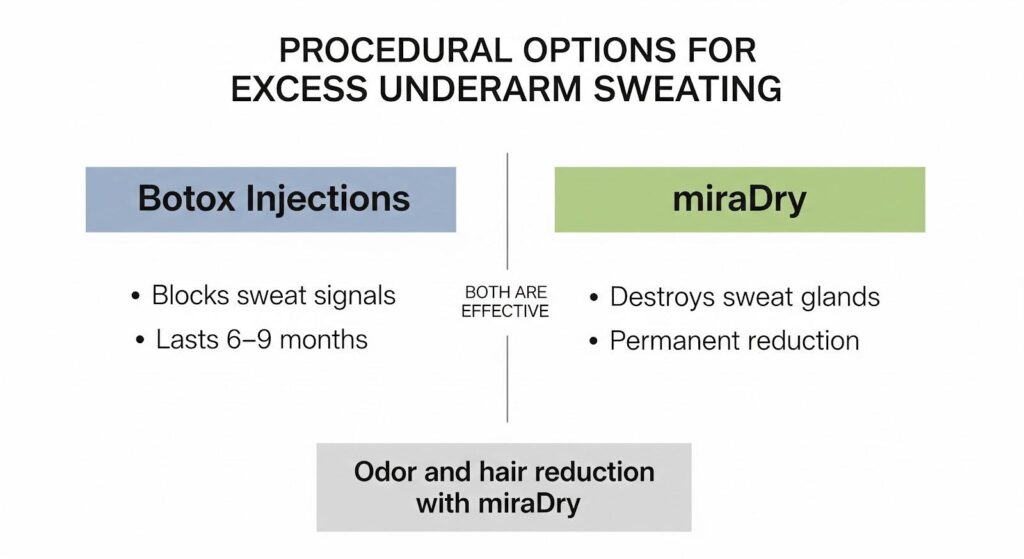

When topical treatments are not enough, two procedures offer durable sweat reduction:

Botulinum toxin A injections: Botox blocks the release of acetylcholine at sweat glands, reducing underarm sweating for 6 to 9 months. The procedure is quick, and most people tolerate it well. Repeat treatments maintain results.

Microwave thermolysis (miraDry): This FDA-cleared procedure uses microwave energy to permanently destroy sweat glands in the armpits.

A head-to-head trial comparing miraDry to Botox found similar sweat reduction at one year, but 76% of patients preferred miraDry because it also reduced odor and hair growth. The procedure typically requires one or two sessions under local anesthesia, with temporary swelling and numbness that usually resolve within weeks.

Both options are effective. Botox is reversible and repeatable, while miraDry offers a more permanent solution with added benefits for odor and hair.

Step 6: When to Switch ADHD Medications

If sweating remains functionally impairing despite all the above steps, switching your ADHD medication is a reasonable next move. Clinical guidelines support trying a different stimulant when one is poorly tolerated.

A randomized crossover study in young adults found that optimized doses of extended-release methylphenidate and Vyvanse produced similar improvements in driving performance and ADHD symptoms.

This means switching from Vyvanse to a methylphenidate-based medication can maintain your symptom control while potentially reducing sweating.

Non-stimulant options like atomoxetine or extended-release guanfacine are also effective for ADHD and may be better tolerated if stimulants consistently cause side effects.

Step 7: Use Systemic Anticholinergics With Caution

Oral anticholinergic medications like oxybutynin can reduce sweating throughout the body, but they come with significant drawbacks. Side effects include dry mouth, constipation, blurred vision, and cognitive effects.

More importantly, blocking sweat production can impair your body’s ability to cool itself, increasing the risk of heat exhaustion or heat stroke during exercise or in warm weather.

For these reasons, systemic anticholinergics should be reserved for short-term use or when other options have failed. If you do use them, your doctor should counsel you on recognizing heat-related symptoms and staying cool.

Practical Tips You Can Start Today

- Check your medicine cabinet: Review all medications and supplements with your doctor to identify interactions that might worsen sweating.

- Cut caffeine gradually: Reduce intake over a week to avoid withdrawal headaches.

- Apply antiperspirant at night: This allows the active ingredients to work while you sleep.

- Keep a sweat diary: Note when sweating is worst to identify patterns related to dose timing, activity, or environment.

- Stay cool: Use fans, wear breathable fabrics, and avoid overdressing.

- Hydrate: Drink plenty of water, especially if you are sweating more.

When to Call Your Doctor?

Contact your healthcare provider if you experience:

- Sweating that started or worsened after beginning Vyvanse or another medication

- Sweating accompanied by fever, muscle twitching, confusion, or diarrhea

- Sweating that interferes with work, social activities, or sleep

- No improvement after trying antiperspirants and hygiene measures

- Interest in exploring topical anticholinergics or procedural options

Seek emergency care immediately if you develop symptoms of serotonin syndrome, especially after adding or increasing a serotonergic medication.

The Bottom Line on Vyvanse Sweating

Vyvanse can increase sweating in some people by raising arousal, heat production, and sympathetic nervous system activity.

While sweating is not a common side effect in clinical trials, individual factors like caffeine intake, medication interactions, and underlying sweat gland sensitivity can make it a real problem.

The good news is that effective solutions exist. Most people can manage Vyvanse-related sweating without stopping their ADHD medication by removing triggers, optimizing their dose, and using targeted underarm treatments.

Topical antiperspirants and anticholinergics work well for localized sweating, while procedural options like Botox or miraDry offer lasting relief when needed. If sweating remains intolerable, switching to a different ADHD medication is a safe and guideline-supported option.

You do not have to choose between controlling your ADHD and staying comfortable. With the right approach, you can manage both.

If excessive sweating or other side effects are affecting your quality of life, you deserve support that addresses the whole picture.

At MARR, we understand that successful recovery means treating not just addiction but the co-occurring challenges that come with it. Reach out MARR today to learn how our evidence-based programs can help you build a healthier, more balanced life.